Public policy advocacy is a constant wrestle between precision/rigour and clarity. I thought my recent piece on the GoldBod losses saga was comprehensive, and therefore convenient. But even finance-steeped friends reached out to advise that I need to get more focused.

Three key questions, in their view, are confusing people, and clearing them up would do far more good for the important debate than discussing “accounting treatment” disputes.

The Questions

How exactly did GoldBod incur losses?

Even if GoldBod incurred losses, are they significant?

But even if significant losses have occurred, aren’t they vastly offset by the benefits of the Cedi’s stability in recent years?

Questions 2 and 3 are, obviously, tightly linked.

I will try and be super-focused and just walk readers through my reasoning without any philosophical meandering.

The Answers

Part I: How did the losses come about

According to the IMF, GoldBod sold about $5 billion to the Bank of Ghana (BoG) “aggregated” from small-scale and artisanal (ASM) gold miners.

2. It also bought $2.6 billion from legacy sources, including large-scale mining companies, outside the GoldBod channel.

https://googleads.g.doubleclick.net/pagead/ads?gdpr=0&client=ca-pub-6034552436546687&output=html&h=280&adk=144910138&adf=3867162050&pi=t.aa~a.2067693828~i.10~rp.4&w=750&fwrn=4&fwrnh=100&lmt=1767078153&rafmt=1&armr=3&sem=mc&pwprc=4282796847&ad_type=text_image&format=750×280&url=https%3A%2F%2Fcitinewsroom.com%2F2025%2F12%2Fbright-simons-writes-is-talk-of-losses-by-goldbod-just-abstract-drivel%2F&fwr=0&pra=3&rh=188&rw=750&rpe=1&resp_fmts=3&fa=27&uach=WyJXaW5kb3dzIiwiMTkuMC4wIiwieDg2IiwiIiwiMTQzLjAuNzQ5OS4xNzAiLG51bGwsMCxudWxsLCI2NCIsW1siR29vZ2xlIENocm9tZSIsIjE0My4wLjc0OTkuMTcwIl0sWyJDaHJvbWl1bSIsIjE0My4wLjc0OTkuMTcwIl0sWyJOb3QgQShCcmFuZCIsIjI0LjAuMC4wIl1dLDBd&abgtt=6&dt=1767078152923&bpp=1&bdt=1424&idt=2&shv=r20251211&mjsv=m202512100101&ptt=9&saldr=aa&abxe=1&cookie=ID%3Dd59a329af1a768cc%3AT%3D1760952318%3ART%3D1767078147%3AS%3DALNI_MYxcb8z1cNCnqQFXD0c-5evcTRi7A&gpic=UID%3D000012bb277246cd%3AT%3D1760952318%3ART%3D1767078147%3AS%3DALNI_Mb97xZqFBLN8cYwmoDuHMD3iw_rvQ&eo_id_str=ID%3D57556b0cc541e79e%3AT%3D1754125463%3ART%3D1767078147%3AS%3DAA-AfjZOSpyb0GB8EN97MepSSmdq&prev_fmts=0x0%2C1200x280%2C1005x124%2C135x506%2C158x593&nras=5&correlator=8111627768427&frm=20&pv=1&u_tz=0&u_his=1&u_h=864&u_w=1536&u_ah=816&u_aw=1536&u_cd=24&u_sd=1.25&dmc=8&adx=190&ady=2614&biw=1521&bih=730&scr_x=0&scr_y=638&eid=31096042%2C95366174%2C95376241%2C95378750%2C95379902%2C95372615&oid=2&pvsid=8985555386560615&tmod=541441826&uas=3&nvt=1&ref=https%3A%2F%2Fcitinewsroom.com%2F2025%2F12%2Fbright-simons-writes-is-talk-of-losses-by-goldbod-just-abstract-drivel%2F&fc=1408&brdim=0%2C0%2C0%2C0%2C1536%2C0%2C1536%2C816%2C1536%2C730&vis=1&rsz=%7C%7Cs%7C&abl=NS&fu=128&bc=31&plas=135x656_l%7C158x656_r&bz=1&pgls=CAEQBBoHMS4xNjguMA..~CAEQBRoGMy4zMy41~CAEQBg..&num_ads=1&ifi=6&uci=a!6&btvi=4&fsb=1&dtd=511

3. It then spent about $10 billion intervening in the foreign exchange (FX) market to deliver the Cedi stability Ghanaians are now enjoying.

4. It still has ~$11.4 billion of “reserves”, of which at least $3.58 billion is made up of gold bullion. I say “at least” because BoG uses a conservative valuation for its gold holdings. Using spot prices today (not advisable) would imply $5.3 billion of gold in over $13 billion of reserves.

5. Trust me, all these numbers are relevant. You will soon see, so keep track.

6. The IMF says that the gold that was bought from local ASM miners led to a loss of 4.28% ($214 million). That is to say the dollar value of the Cedis supplied by the BoG to the miners through GoldBod and the dollars delivered to the BoG from the overseas buyers (we shall call them “off-takers”) don’t match; there is a shortfall.

7. (Note: we are all dependent on the IMF’s data because the IMF is the only entity the government would give such data to.)

8. How that arises is not difficult to explain at all. I will walk readers through two hypothetical transactions using real market numbers for two separate days.

9. Let’s start with 10th December 2025.

The LBMA benchmark for 24 carats/K gold (think of this as the “global price for pure gold”) was: USD 4,196 per troy ounce (think of this as the unit in which gold is sold internationally).

The official exchange rate used by GoldBod: 11.42 GHS/USD GoldBod price per Ghana pound (23 carats/K) was: GHS 11,446 (the “Ghana pound” is the main local unit for gold; 23 carats is the usual assay benchmark locally).

The now famous bonus offered by GoldBod to local miners to encourage them to sell: GHS 650 per Ghana pound of 23K.

Convert 23K “pound” to 24K equivalent = 11,943.652 GHS per Ghana pound of 24K

Convert Ghana pound to ounces = 47,934.078 GHS

Convert to USD = USD 4,197.380

The result is a tiny premium (GoldBod is paying more for local gold than it can sell internationally).

Premium vs 4,196 = USD 1.38/oz; Percent = +0.033%

Now add the bonus on top of the 23K price per Ghana pound: 11,446 + 650 = 12,096 GHS (23K)

Convert to 24K equivalent = 12,621.913 GHS (per Ghana pound of 24K)

Convert to troy oz = 50,656.178 GHS per troy oz (24K)

Convert to USD = USD 4,435.742

Premium = 4,435.742 − 4,196 = USD 239.742 per ounce

Percent = 239.742 / 4,196 = 5.714%

10. So, on that day, GoldBod lost 5.714% just on the buying side. Even if it had sold at the full international price, it would still have lost money. We shall explain in a moment why it can’t really sell at the full international price, either.

11. Now, let’s take today, the 29th of December.

GoldBod quotes GHS 11,467 per Ghana pound

Per ounce equivalent = GHS 46,023.112

Per USD per ounce at official exchange rate of 11.10 = USD 4,146.22

Compare to the “world market price” of USD 4,325

Implied Discount (GoldBod is making a marginal profit) = USD 178.774

In percentage terms = 4.13% discount

But remember the bonus!

With bonus = GHS 12,117 total per Ghana pound

Ounce equivalent = GHS 48,631.789

USD equivalent = USD 4,381.242

Implied Premium = USD 56.242

Premium % = 1.30% premium (GoldBod is making a loss of 1.30% per trade)

Ghana travel guide

12. It should be obvious what is happening here: ASM gold was a relatively efficient market in Ghana for many years with many buyers and many sellers until GoldBod was imposed on the system. The miners were used to getting as much of the “world price” as possible. They sold through lean, mean, and highly efficient intermediaries with very low costs who could time the onward sale to maximise their margin.

https://googleads.g.doubleclick.net/pagead/ads?gdpr=0&client=ca-pub-6034552436546687&output=html&h=280&adk=144910138&adf=3167537780&pi=t.aa~a.2067693828~i.22~rp.4&w=750&fwrn=4&fwrnh=100&lmt=1767078155&rafmt=1&armr=3&sem=mc&pwprc=4282796847&ad_type=text_image&format=750×280&url=https%3A%2F%2Fcitinewsroom.com%2F2025%2F12%2Fbright-simons-writes-is-talk-of-losses-by-goldbod-just-abstract-drivel%2F&fwr=0&pra=3&rh=188&rw=750&rpe=1&resp_fmts=3&fa=27&uach=WyJXaW5kb3dzIiwiMTkuMC4wIiwieDg2IiwiIiwiMTQzLjAuNzQ5OS4xNzAiLG51bGwsMCxudWxsLCI2NCIsW1siR29vZ2xlIENocm9tZSIsIjE0My4wLjc0OTkuMTcwIl0sWyJDaHJvbWl1bSIsIjE0My4wLjc0OTkuMTcwIl0sWyJOb3QgQShCcmFuZCIsIjI0LjAuMC4wIl1dLDBd&abgtt=6&dt=1767078152928&bpp=1&bdt=1429&idt=1&shv=r20251211&mjsv=m202512100101&ptt=9&saldr=aa&abxe=1&cookie=ID%3Dd59a329af1a768cc%3AT%3D1760952318%3ART%3D1767078147%3AS%3DALNI_MYxcb8z1cNCnqQFXD0c-5evcTRi7A&gpic=UID%3D000012bb277246cd%3AT%3D1760952318%3ART%3D1767078147%3AS%3DALNI_Mb97xZqFBLN8cYwmoDuHMD3iw_rvQ&eo_id_str=ID%3D57556b0cc541e79e%3AT%3D1754125463%3ART%3D1767078147%3AS%3DAA-AfjZOSpyb0GB8EN97MepSSmdq&prev_fmts=0x0%2C1200x280%2C1005x124%2C135x506%2C158x593%2C750x280&nras=6&correlator=8111627768427&frm=20&pv=1&u_tz=0&u_his=1&u_h=864&u_w=1536&u_ah=816&u_aw=1536&u_cd=24&u_sd=1.25&dmc=8&adx=190&ady=4232&biw=1521&bih=730&scr_x=0&scr_y=1329&eid=31096042%2C95366174%2C95376241%2C95378750%2C95379902%2C95372615&oid=2&psts=AOrYGslDSBldbCQp36or2eeT_3B7w44TWlSk4gaRHeaueLau0v7AEbhDUeRPKdKFJhVFzmiZ5zOP1xEyksXoSvoCcUpLRPdpPAijmcak1ISgMgp34I1MGCOSXF_WRFm5ADv1cdR_%2CAOrYGskLjPQQfSe8QmD_7I2NEN6uhHNs6qhZ0F2OLryoijXtG7LTox5ukRg1YSffD5ZytcdGzakujJisgjpTdJqNSflMquYZbYT3BVOqgeDeqhtOP3F1qcgNF3H5UxTPHsXSng3x%2CAOrYGslJovRxMbU4iF63CTdV-BCfrrNOCknon9tuWEjUWuRB9F0qKdbEI1rVUUA_NWuGK23wOa_VkfWW7nE2pWWFja4BGdSSbAwMnpDrwpgyycuvAIjvcEGnAUtUwWLWDC2SGYar&pvsid=8985555386560615&tmod=541441826&uas=3&nvt=1&ref=https%3A%2F%2Fcitinewsroom.com%2F2025%2F12%2Fbright-simons-writes-is-talk-of-losses-by-goldbod-just-abstract-drivel%2F&fc=1408&brdim=0%2C0%2C0%2C0%2C1536%2C0%2C1536%2C816%2C1536%2C730&vis=1&rsz=%7C%7Cs%7C&abl=NS&fu=128&bc=31&plas=135x656_l%7C158x656_r&bz=1&pgls=CAEQBBoHMS4xNjguMA..~CAEQBRoGMy4zMy41~CAEQBg..&num_ads=1&ifi=7&uci=a!7&btvi=5&fsb=1&dtd=2367

13. In the current model, GoldBod buys all the gold in the ASM market and must be ready to buy at all times and deliver to offtakers in all weather. It must offer close to market rate across the board all lose to smugglers or from miners and local traders just hoarding the gold. On the domestic, buying, side, things are that simple.

14. On the external, selling, side, GoldBod must sell at a discount to World prices because one has to factor in freight, insurance, and the assay verification and other costs on the importer’s side since this is the dore (raw gold) market outside a trusted exchange. The importer/offtaker takes a risk and must be compensated.

15. The importer/offtaker also advances dollars to the Bank of Ghana/GoldBod because the liquidity needs of the BoG are pressing and fast settlement is vital for that reason. That is also a risk that the offtaker must be compensated for.

16. In India, dore gold has favourable customs treatment because the Indian government wants to promote refining in India. If the gold was being refined in Ghana, GoldBod would have been hit by additional discounts because the importer/offtaker’s custom duties would have increased.

17. In short, when you displace a large, heterogenous, group of buyers, sellers, and intermediaries, with a very concentrated ecosystem of a super-aggregator (Bawa Rock), a few mega offtakers in India and Dubai, and one ultra-intermediary (GoldBod), you can get efficiency but risks can also concentrate and by the time you compensate for those risks, there would be losses.

Part II: Are the losses even significant?

18. If GoldBod was operating strictly using its own capital, yes!

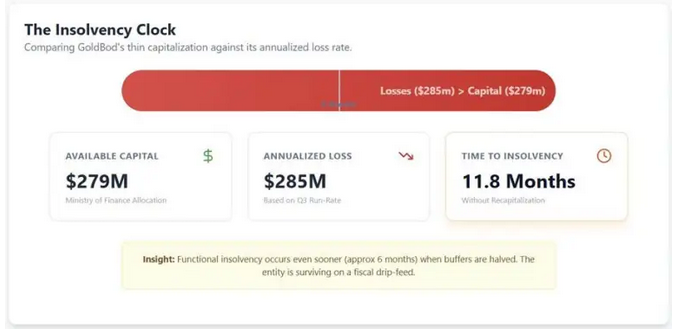

19. In 2025, GoldBod was allocated $279 million as working capital but the Finance Ministry did not disbursed. We can interpret this to mean that the Ministry was unclear about its trading strategy of model.

20. But assuming it had disbursed and this was the only fiscal buffer available to the GoldBod, not the limitless-seeming Bank of Ghana tap. Then:

Consider losses on the ASM doré leg at US$214 million through end-Q3 2025 (i.e. about 9 months).

Annualising that run-rate gives roughly:

In effect, it would take 12 months for GoldBod to become functionally insolvent if it continued operating at the same scale and loss structure.

Do you realise though that the Ministry of Finance would be forced to recapitalise it due to political reasons? You see why some of us are arguing that this is a fiscal subsidy that must be transparently borne by the policy owners?

In fact, a more conservative “functional insolvency” trigger is when half the buffer is gone.

Half of US$279m = US$139.5m.

At ~US$285m/yr loss rate:

Operationally: you would expect serious stress within ~6 months, and likely failure within ~12 months, absent a bailout or a major restructuring of the model.

21, Remember that Cocobod is a policy institution too. Yet, we have all been witnessed to how capital stress has damaged it.

22. Using SIGA and Auditor General reports, we have attempted to construct similar loss-per-turnover numbers for Cocobod below.

23. See the numbers for Cocobod below:

24. As readers can judge themselves, Cocobod records significantly lower losses benchmarked against the reported GoldBod losses.

25. The self-evident implication is that even as a policy organ of the government of Ghana (GoG), a consistent near- 5% loss on annual turnover by any would seriously stress its sponsoring government.

26. Bear in mind that the loss prospect could amplify if a single off-taker refused delivery, a prospect far from remote given the current level of concentration.

Part III: But don’t the benefits far outweigh the costs?

27. This is obviously the most complex part of the analysis. But if readers bear with me and follow the numbers, they should be fine.

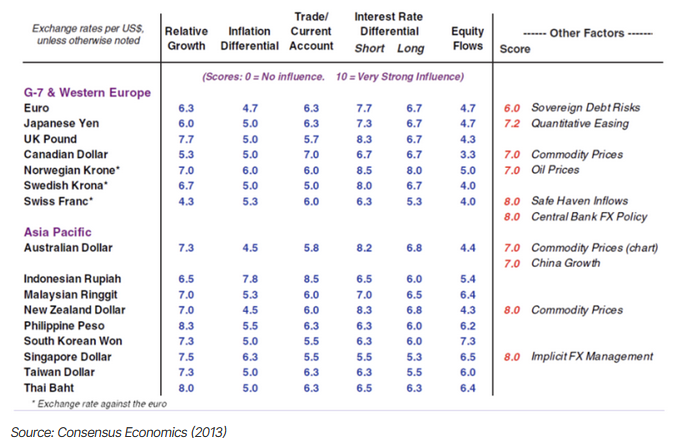

28. It is a trivial point for everyone to grasp regardless of their economics knowledge that no one factor alone explains exchange rate movements. Surveys of economists by popular research houses normally surface more than 15 major factors.

29. In Ghana, we know that the fiscal deficit and how it is financed, inflation, export performance, and a whole host of factors both influence the exchange rate and are in turn influenced by it.

30. No serious person would thus attribute the stability being enjoyed by the Cedi so far to just one factor, such as the policy innovation represented by the GoldBod.

31. The right question thus is: how much of the Cedi’s stability should we attribute to the GoldBod and through what mechanism has it been exerting its influence? (Some of us have held the position for a while now that the Ghana Cedi is overvalued, and that it has moved from a generally managed float regime to a substantially managed peg one. But that is a separate debate. What is relevant is twofold: a) how the government found the capacity to manage the peg (never a trivial undertaking as the UK learnt on Black Wednesday) and b) whether macro-indicators, such as inflation, move in a manner that makes the peg sustainable.)

32. First, we know that the only plausible mechanism is through the “gold dollars” the GoldBod has diverted from commercial banks and parallel forex markets (which used to get most of the dollars from ASM gold, including even the smuggled portion since smugglers still need Cedis eventually to continue their nefarious trade) to the central bank. The BoG uses these dollars to cushion the Cedi.

33. Remember, however, that only about half of the funds used by the BoG to intervene in the FX market comes from the GoldBod. The remaining 50% comes from other exporters and large-scale gold mines, as well as IMF and other official financial flows. So, whatever impact we attribute to the BoG’s interventions (and remember that intervention alone can never halt depreciation), 50% is what we must attribute to the GoldBod.

34. Second, we know that gold prices have risen dramatically. This has nothing to do with the GoldBod but it is on course to nearly triple the amount of gold dollars in the system compared to, say, 2023.

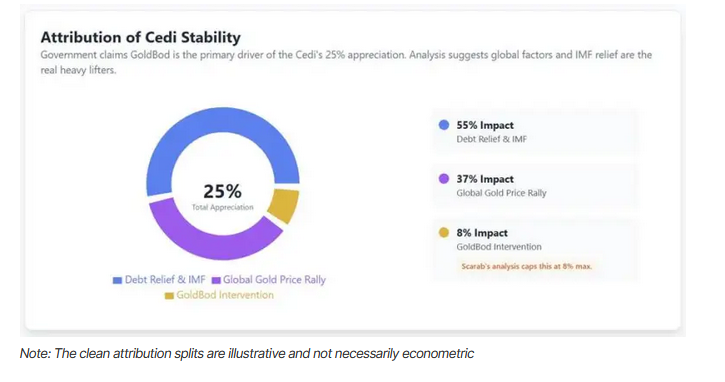

35. If we use year-end values, the Cedi has risen from 14.7 (2024/12) to the US dollar to 11.14 to the US dollar (2025/12). That is a near -25% appreciation rate.

36. From the historical gold-Cedi relationship, we estimate a lagged effect of 3.9 percentage points appreciation in the Cedi if gold prices rise by 10%. The financial return on gold in 2025 is ~72%. Through a complex series of technical calculations to fix temporality and directionality, we estimate that 8.4% of the Cedi’s appreciation is due to the rise of the gold price through the export channel.

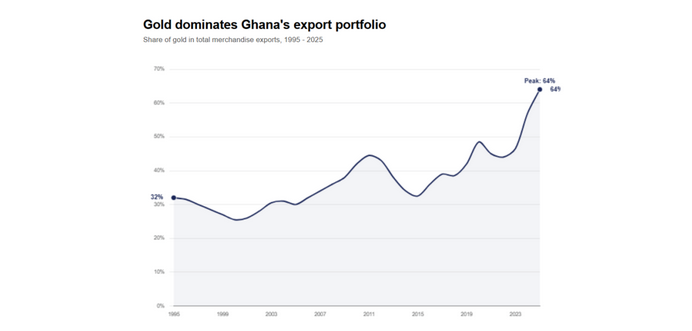

37. It is important to note that gold as a share of exports in Ghana has risen from the mid-30% range about two decades ago to roughly 65% today (double the long-run 2-decade average), a sign of insane overdependency on the commodity’s price rally.

38. The simple result of the above analysis to isolate the GoldBod’s effect is that of the ~25% appreciation rate, the GoldBod must share with other factors a maximal bound of 8% (that is half of the positive residual after accounting for the gold price rally’s effect on export performance).

39. A lot of other complex calculations follow to determine the impact to be allocated to the IMF-supervised fiscal consolidation and primary balance enforcement and its influence on money supply; the impact of the improved harvests (primarily a function of rainfall) on food inflation; the debt restructuring effort and the resulting relief from debt servicing; and the fall in interest rates, which appears to have been primarily driven by Finance Ministry policy. All these have had some complex direct or indirect effect on the Cedi.

40. It would be difficult in light of all the above to assign more than 3 percentage points of the 25% Cedi appreciation to the role the GoldBod has played in resourcing the Bank of Ghana’s FX market intervention capacity. Even those who will disagree with this specific estimate cannot dispute the logic of capping GoldBod’s contribution.

41. A 3% appreciation corresponds to about $600 million in relief on the import bill front. A significantly higher number than the $214 million we have been quarreling about.

42. Don’t get me wrong. It is a significant new development that we must all respectfully follow. But it serves no one’s interest, lest of all GoldBod management’s, if we start blowing up expectations. That would amount to setting them up to fail.

43. But we must not be oblivious about the costs of central bank intervention. The cost-benefit ledger extends to that aspect too. As I will show shortly, things don’t end at $600 million in “import burden relief”. Relax, I am not going to try and offset the relief with any speculative symmetric pressure on exporters. There is something more interesting to explore.

44. When BoG (via GoldBod) purchases gold locally in Cedis, it creates new Cedi liquidity. If BoG sterilises (mops up) that liquidity through Open Market Operations (OMO), it converts a monetary expansion into a recurring interest expense.

45. OMO simply means it borrows money from banks and other large institutions to “back” the paper money it has created (keeping things simple.) That money doesn’t come free.

46. On a US$5 billion gold purchase base, sterilising the Cedi created by that purchase through OMO transactions costs the central bank roughly GHS 11–13bn every year at realistic BoG OMO rates.

47. It is thus possible that the BoG will announce losses for this year. In addition to all the opacity and shadowy dealings, these fiscal stresses are the reason why some of us have been consistently wary and apprehensive about all these gold programs. Who has noticed that since the Gold-for-Oil program was terminated there has been no discernible impact at the fuel pumps? Who really was that program serving?

48. Remember also that we have only accounted for GoldBod losses in the Gold-for-Reserves intervention program. If even the other half of the intervention budget implies half of GoldBod’s trading losses, the total costs of the program would easily neutralize the $600 million in import burden relief calculated earlier (not accounting for sterilization costs of the other half of the intervention budget to avoid double-counting).

49. In simple terms, the GoldBod-backed intervention program yields no net benefit to the extent that it does not cover enough of the BoG’s need nor alleviate import burden sufficiently.

50. But that is still in neutral territory. It implies, at worst, that the GoldBod approach once its full costs become transparent cease being the miracle that on the surface it appears to be.

51. There is a more worrying issue. The GoldBod-backed intervention program is generally cost-neutral only whilst the price of gold remains elevated.

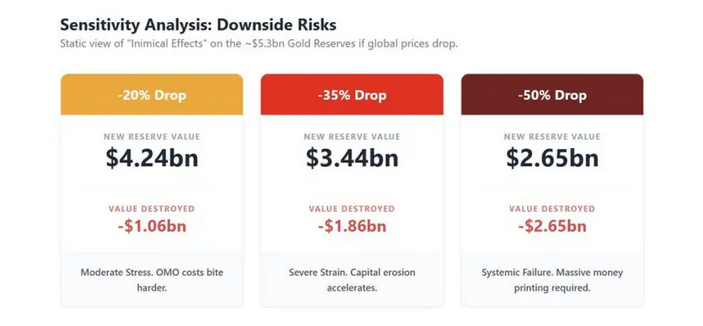

52. Readers may recall that the BoG stores some of the gold in its reserves and relies on a liquidity conversion cycle to turn the gold dollars into a cedi cushion in the domestic FX markets. Imagine a sudden drop in the price of gold, perhaps to its historic two-decade mean in the $2000-ish range.

53. Because of the policy commitments, BoG cannot simply suspend the program in its entirety. Not when funds have been advanced and long- or medium-term supply obligations have been established.

54. In such a bear market downside scenario, the BoG’s gold reserves would suddenly lose value in the multibillion-dollar range.

55. Gold bought at the height of the market could then only be liquidated for Cedi cushioning at less than half their value. That would imply printing even more Cedis to underwrite the effort. It is unbelievable how pro-cyclical the whole thing is until you work through all the risk-scenarios.

56. To repeat: the whole GoldBod thing can persist in a reasonably contained manner if the price of gold stays high and volatility continues to tilt upwards than downwards most of the time.

57. A significant drop in the price of gold would hit the program very hard. But then again the entire export channel will implode anyway.

58. Gold is now the real risk-driver for the economy. An important lesson in all of this is that the country should stop bifurcating its budget design into oil and non-oil and use gold and non-gold.

59. As for GoldBod, the more transparency there is, the better prepared this country would be when the markets turn and deft navigation is needed to prevent it from skidding off the tracks.

60. Hopefully, this tightly focused piece has done a better job in addressing the three questions on the minds of many readers.

Source: www.kumasimail.com